The Presses

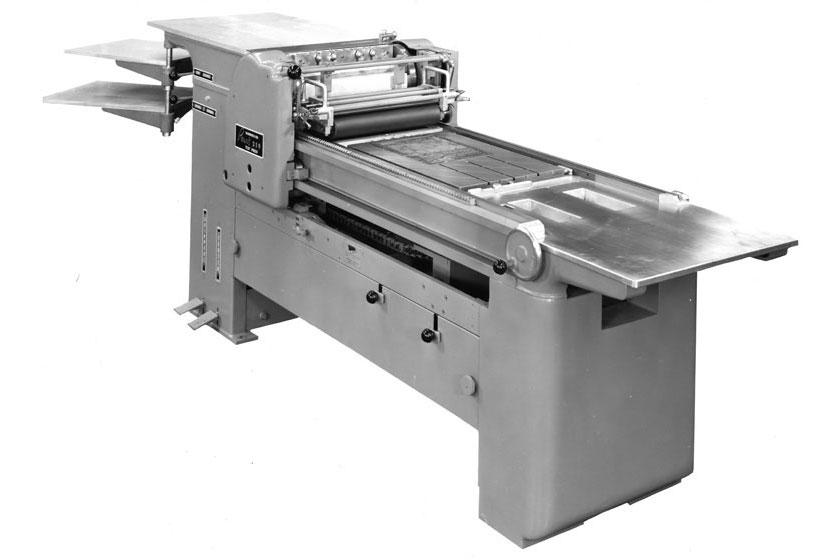

Vandercook 219

Tech Specs from vandercookpress.info

- 4/15/49 SN: 10507 – 7/9/58 SN: 18486

- Our SN: 17954

- Bed: 19″ × 42½″

- Maximum sheet: 18¾″ × 28″

- Maximum form: 18″× 24″

- Floor space: 2’8″ × 10’9″

- Weight: Weight: 3100 lb

- Bed adjustable within .240″ range. Powered impression cylinder — pressing the clutch pedal sends it back and forth. Motor-driven ink drum. Adjustable cylinder stops for short or long forms. Optional automatic frisket/sheet delivery. Optional can-fed automatic ink feed.

The 219 has more or less taken over as the main workhorse in our shop. Although this is a power-driven press, parts have been acquired to convert the press back to manual operation (I just haven't gotten around to the conversion...). This model of the 219 has, like the 15-21, an adjustable bed, but the main advantage here is the larger sheet size, allowing a wider book to be printed head-to-tail. It also has those handy swivel shelves, which allow for fresh and printed sheets to be kept separate without fighting for position on the feedboard.

The press was acquired from Oregon Engraving, who had it (but used it very little) for most of its life. Bringing the press home involved a rather painful and ridiculous ordeal at the US border, which was thankfully followed by a hurried, exhausted, somewhat delirious but much appreciated stay with Rebecca Gilbert and Brian Bagdonas of the C.C. Stern Foundry / Stumptown Printers in Portland. The return trip, on the other hand, found me with a Canadian Customs official who was quite possibly the most friendly and helpful person I've ever met. Oh, and, trust me, 17ft U-Hauls do not like lugging these things up hill.

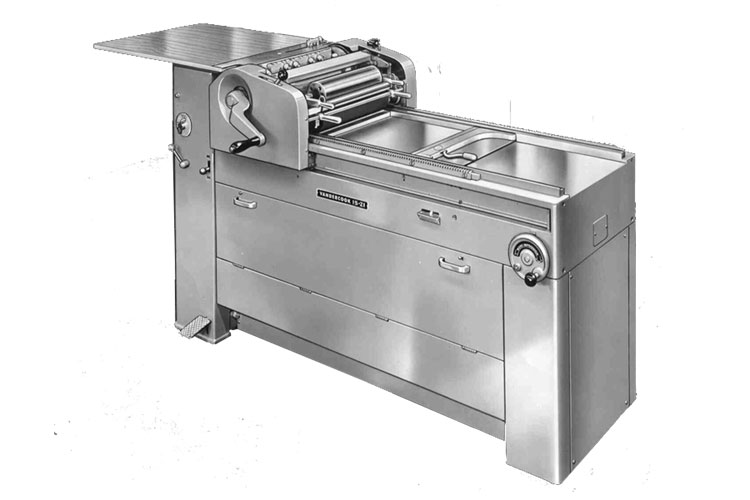

Vandercook 15-21

Tech Specs from vandercookpress.info

- 5/13/55 #17,734 - 11/25/58 #18,930

- Our SN: 18926

- Bed: 15½" × 24¾" '

- Maximum sheet: 15¼" × 23"

- Maximum form: 14½" × 21"

- Floor space: 7' × 2'2"

- Weight: 1875 lb

- Bed adjustable within .240" range. Automatic short travel cylinder trip, "making it unnecessary to travel the cylinder the full length of the bed when proving forms up to 14" long. The full 21" printing length can be obtained by merely traveling the cylinder to the end of the bed" (this sounds like you don't have to adjust a cam). The tray at the right end is for washing rollers. There is a niche in the bed for a plunger solvent can.

The 15-21 was our main production press from 2008-2016, and is still in heavy rotation. Similar in bed-size to the popular SP-15, the 15-21 has the added feature of an adjustable bed, which allows the bed of the press to be raised and lowered depending on the height-to-paper of the surface being printed. This has come in very handy with type brought back to Canada from Europe, which does not conform to North American type height. One of our projects that involved some tricky issues with type height was Michael Ondaatje's book Tin Roof, production details of which can be found here.

Our 15-21, and all its trimmings, was handed down all too generously by Caryl Peters of the Frog Hollow Press in Victoria, BC.  I first met Caryl around 2001, when we were both early in our bookmaking careers, and over time a mutually beneficial working relationship and close friendship developed based on a love of fine books, typography and printing. In exchange for various menial computer-related tasks that I helped Caryl with (website updates, etc.), she was kind enough to begin a casual mentorship, apprenticing me in the rudimentary points of press-work (which she, herself, had been taught by Jan & Crispin Elsted at the Barbarian Press in Mission, BC.

I first met Caryl around 2001, when we were both early in our bookmaking careers, and over time a mutually beneficial working relationship and close friendship developed based on a love of fine books, typography and printing. In exchange for various menial computer-related tasks that I helped Caryl with (website updates, etc.), she was kind enough to begin a casual mentorship, apprenticing me in the rudimentary points of press-work (which she, herself, had been taught by Jan & Crispin Elsted at the Barbarian Press in Mission, BC.

A handful of years later Caryl ran into some shitty luck, and both the press and her health faltered in 2006. The press, which for no apparent reason began printing inconsistently, turned into a source of intense frustration for which Caryl could find no simple solution: no amount of internet searching, hired help, or trial and error could get the press in a condition to produce even a single decent print.

This went on for months. At the same time, Caryl's health suddenly required significant and relatively immediate attention, which, after months of wrestling with the press, found her up against two intense forms of uncertainty, and with that she was off to Vancouver for treatment.

While away, I hit the internet, and also hit Caryl's basement with a toolbox and a stupid idea that I could fix the damn press. Each Saturday for 6 weeks I spent the afternoon slowly taking the press apart, one piece at a time, working carefully from a set of schematic diagrams that had come with the press when Caryl purchased it from Don Black Linecasting in Toronto.

I first scanned the diagrams and enlarged them, and each Saturday I'd use them as a map in the dismantling of a piece of machinery which, if fussed with enough, would likely never work again.

Over the 6 weeks I found myself often frustrated by parts that wouldn't budge, trapped by decades of ink build-up and wear, but blind and stupid initiative would eventually blunder through, and, bloody-knuckled and poisoned by solvent, I eventually took a guess at the cause of the problem. This process, of course, was much aided by a handful of wise and long-educated Vandercook experts (especially Fritz Klinke at NAGraphics, Paul Moxon of Vandercookpress, and Gerald Lange of the Bieler Press), and by the time Caryl returned home, the press was repaired, cleaned, and ready to roll.

Over the next year, Caryl's health continued to be an issue, and, less and less able to operate the press, it began to spend much of its time sleeping. At the same time, I began plans to move back to the Okanagan, and Caryl decided it was time for the press to find a new home as well. This was bitter-sweet for all of us: Caryl and I had come to count on our Saturdays together, to talk type and eat Ricola cough drops, and our looming separation meant an end to these weekend visits. And then there was the Vandercook: I couldn't imagine how difficult it would be for Caryl to let go of her press, so that receiving it felt like some sort of betrayal. Of course, it wasn't doing anyone any good sitting idle in Caryl's basement, and despite my concerns there was also a sense of obligation and respect that left me feeling both appreciative and, in a strange way, accountable: to carry on the good work that Caryl had done. I have tried my best to do so, and continue on with that goal.